July 1, 2015

Olympic Village plans envision replacing Kosciuszko Circle with new road system

Olympic Village plans envision replacing Kosciuszko Circle with new road system

Boston 2024’s Olympic Games organizers have proposed a $160 million publicly funded fix for the difficult-to-navigate and difficult-to-pronounce Kosciuszko Circle traffic rotary. Already a critical link for commuters into and out of Boston, the circle where Morrissey Boulevard, Old Colony Boulevard, Day Boulevard, and Columbia Road converge would, if the Games get the go-ahead, receive a massive makeover to make it ready for its prime-time role as the gateway to the Athletes’ Village on Columbia Point.

The question of how to “fix” Kosciuszko Circle has never really been addressed by city, state, or civic-level planners, even as large-scale planning initiatives have considered ways to transform the rest of the peninsula.

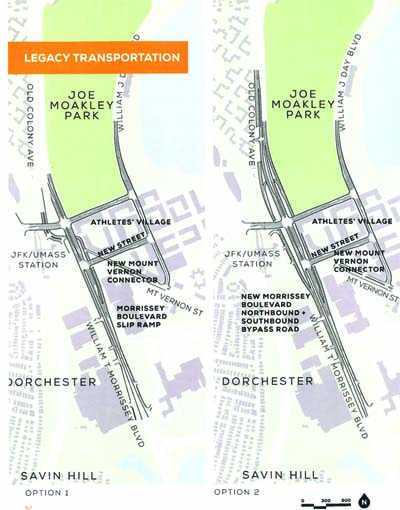

On Monday, Boston 2024 rolled out its current vision for transforming Columbia Point to accommodate an Athletes’ Village. Their so-called “Bid 2.0” plan calls for eliminating the rotary and replacing it with a four-way intersection. Still in a conceptual phase, the proposal would aim to untangle roadways in and around the circle, alleviating the congestion that comes with it – a move, Boston 2024 says, that has long been talked about by local residents and their elected officials.

But no actual study or engineering plan has ever been put in place to detail exactly how a new road system would work — and there has been no decision on whether the rotary should be replaced or simply augmented with new roads.

The Columbia Point Master Plan, from which “Bid 2.0” borrows heavily, was generated in 2011 after a multi-year community process that was organized by the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA). The study, set up to inform development on Columbia Point over the next 20 to 25 years, does not recommend any specific fix for Kosciuszko Circle (the name, pronounced koh-shuz-ko, celebrates the Polish military leader Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who fought in the American Revolution as a colonel in George Washington’s Continental Army).

In fact, the renderings released on Monday are thought to be the first designs that address what a reconfigured circle might look like.

“The master plan did not have a fix for Kosciuszko Circle,” said Don Walsh, a Columbia Savin Hill resident who chaired the task force that formulated the document. “It just said that if the plan gets built out anywhere near what we specified, Kosciuszko Circle has to be fixed.”

The goal the master planners had in mind was the separation of local traffic in and around Columbia Point from regional traffic, using Morrissey Boulevard as an alternative to a clogged Expressway, said Paul Nutting, a longtime Savin Hill resident who served on the task force.

“The Olympic plan actually does dovetail pretty well with the master plan,” Nutting said, adding: “The only problem is that master plan had an additional street that crossed Morrissey Boulevard between Santander and BC High.”

The Boston 2024 proposal uses a smaller footprint than the master plan, and organizers would rely on a master developer to build out the Athletes Village. The developer, according to 2024 documents, would be responsible for paying for the estimated $40 million needed reconfigure the Village’s interior streets.

As Nutting noted, the 2011 master plan suggested that a new street connecting Morrissey Blvd. and Day Blvd. be laid out perpendicular to Morrissey south of the Santander Bank property. The Boston 2024 proposals move the new street to the other side of the Santander property, with it cutting across the top of Mt. Vernon Street. Of two renderings, one connects Mt. Vernon to Old Colony Avenue and the other creates a dead end at the top of Mt. Vernon Street, which is cut off by the new street’s intersection with Morrissey and its north and south bypass roads.

Both options presented by Boston 2024 would replace the rotary with a four-way signalized intersection that proponents say will allow for easier pedestrian access to and from the Point. Rich Davey, the CEO of Boston 2024, made the case to the Reporter this week that the traffic rotary is considerably more dangerous than other roads and rotaries in the state. Davey says an analysis of traffic data commissioned by 2024 shows that there have been “over 100 accidents there between 2011 and 2013.”

“You’re three times more likely to get into an accident here than a normal intersection or rotary in Massachusetts,” Davey said. “We think we can use the Games to catalyze the state investment required. Its pretty clear, Games or no Games, this needs to get fixed.”

Reaction to the proposed fix by a small sample of residents and elected officials has been cautiously positive.

“That four-way intersection – I don’t know how well that’s going to work out,” said Paul Nutting. State Rep. Dan Hunt of Dorchester, who was briefed on details of the re-configured rotary and the Athletes Village ahead of “Bid 2.0’s” release, said more work is to be done.

“The improvements to traffic flow and Kosciuszko Circle look intriguing to relieve current congestion, but I think they need to do more in-depth traffic studies on how it affects the roads on the other side,” he said Monday.

Deciding on the right fix poses one hurdle for Kosciuszko rehab planners. Another is the securing of funding for the work and the associated political will and consensus needed to extract the money from an already cash-strapped state with a pipeline chock full of other infrastructure projects.

As Boston 2024 frames it, these infrastructure improvements should happen with or without the Games, despite their absence from Beacon Hill’s list of projects to be done, which is laid out in transportation bond bills crafted every three years or so, or in the Governor’s five-year capital investment plan. The hard look at Kosciuszko is an example, politicians say, of the proposed Games’ catalytic effect on transportation infrastructure planning; it allows the state to focus on projects that would not normally feel the warmth of the spotlight were it not for the prospect of an Olympics in Boston nine years out.

In essence, Boston 2024’s fix for the rotary is starting from scratch: The Department of Transportation does not have “any studies or planning efforts present or past relative to addressing traffic congestion through Kosciuszko Circle,” said MassDOT spokesperson Michael Verseckes on Tuesday. The Department of Conservation and Recreation, the other state agency with oversight at the circle, had no information available as of press time Wednesday.

In total, the improvements needed around Columbia Point that are not currently budgeted by the state could cost as much as $280 million, according to Boston 2024’s projections: The Circle upgrade costs alone would add up to between $120 million and $220 million and JFK/UMass Station improvements would total $40 million to $60 million. The projected public infrastructure investment needed from state coffers for the entire Olympics build-out could reach $775 million statewide, according to current 2024 projections. “It would be a once in a lifetime opportunity to deliver decades’ worth of infrastructure and open space improvements to residents in just nine years,” according to Boston 2024’s executive summary of “Bid 2.0.”

Members of the Dorchester and South Boston delegations at the State House signaled early support for a fix — and a willingness to fight for state dollars — in interviews with the Reporter.

“I think that’s our job to fight for these infrastructure improvements that absolutely wouldn’t happen without the Games. There’s little to no appetite to build a $200 million replacement for Kosciuszko Circle without the Games,” said Dan Hunt, who noted that he and others have been pushing for a $40 million renovation to Morrissey Boulevard and its drawbridge for years, to no avail.

“The state has a role and obligation to fund improvements. And these are priorities that I think are easy to defend and promote,” said state Rep. Nick Collins of South Boston, referring to the Kosciuszko fix. Collins called the rotary a chokepoint at the entrance to the city of Boston that needed fixing and that he “hopes to see something in the FY ‘17-18 capital plan” that will be crafted in 2016.

State Sen. Linda Dorcena Forry, who represents Dorchester and South Boston, said she looks “forward to seeing the governor’s reaction to the report and working collaboratively with his findings.” And if Boston is selected by the International Olympic Committee in September 2017 to host the Olympics, she says, “There is no way we could have the Olympics without that infrastructure in place. If Boston is chosen, she added, “then I will be working hard to make sure that we get that investment. It’s really for the long-term. But I still don’t know if we will get it.”

A state-funded solution to the Circle was not a viable consideration for the men and women who designed the master plan document with the BRA. Concerns about the height and density of new buildings took precedence. Their report called for high-rise apartments along the Expressway and adjacent to JFK/UMass station. The height and density would bring capital and demand attention from developers and elected officials to deliver on the community’s more holistic needs, study co-chair Don Walsh said.

“The master plan made new street grids, made new blocks, and put in a public park there. There were amenities for community. To pay for that, we knew we were not getting the city or state to do it. We had to get the developer to do that. We knew we could because they can go higher and denser than Dot has ever seen before and that was the trade-off,” Walsh said.

Both Walsh and Nutting noted that they are neither Olympic supporters or opponents. “I don’t think we should be afraid of the Olympics. I’m not a proponent, but I’m not an opponent,” said Walsh. “I can see good things, long term. Why not continue the discussion and look at it?”

For Nick Collins, there are other benefits to the Olympic conversation in the city and around the state. “I hope at the end of this process, people can pronounce ‘Kosciuszko’ correctly,” he said. “If nothing else comes out of it, I hope for that.”

Villages:

Topics: