January 13, 2016

But Brian Golden knows that boom times don’t last long

Riding the wave of the city’s largest building boom in a half-century, Brian Golden, the chief of the Boston Redevelopment Authority, expects no let-up in the break-neck pace of new construction starts across the city. He also foresees more tall cranes and excavators in Dorchester’s near future.

There were 14 million square feet of new construction added onto the pipeline in 2015 – a number not seen since the “go-go” days of urban renewal, said Golden, when whole neighborhoods were flattened by his early predecessors.

Golden anticipates that the new year could well soar past the 2015 pipeline mark with a flurry of green-lit projects and new letters of intent for large scale developments, best known in planning and civic circles by their bureaucratic moniker: “Article 80s.”

“It’s an exhausting pace because we’re not just about the business of managing the biggest building boom in the city’s history, but we’re also doing more aggressive comprehensive planning than we’ve done in many years,” said Golden, 50, in an interview with the Reporter. “You’d have to go back a couple of decades before you saw the pace of planning that’s occurring here and that’s in direct response to the mayor’s goal of making the BRA not just Boston’s major real estate development agency but also the planning agency. There’s been a lot of external criticism that planning got short shrift. And this mayor wants to do bona fide comprehensive as well as granular planning at the same time so that we keep a very positive development climate.

Still, Golden isn’t sitting easy on his ninth floor Boston City Hall perch. In fact, he’s a bit anxious, already bracing for the inevitable downturn in the economy and fretting that its largesse will dry up before saturating the outlying neighborhoods where Article 80s are counted with fingers, not Excel tables.

“We’re closer to the end of this economic recovery than the beginning, that’s for sure,” said the former state representative from Allston-Brighton who joined the BRA as a deputy in 2009. “The average life expectancy of a post World War II recovery is 7-8 years. We’re knocking on the door. We want to make sure we get as much value for the people of Boston in as many neighborhoods as we can while this window is still open.”

The window that Golden grasps has widened enough to incorporate “distinct parts of Dorchester” that are poised for major growth: Columbia Point, long stretches of Dorchester Avenue, and the Fairmount line corridor, which could finally flush new dollars, housing units, and jobs into Mattapan and project-starved, lower-income sections of Dorchester as well.

When pressed on whether the Dorchester section of Dorchester Avenue will get the same kind of granular planning effort that is now underway for its northernmost stretch in South Boston, Golden was non-committal. There are “a dozen areas” that could be next in line for such an intense planning exercise, he said. “But today we’re not ready to identify what’s next. That involves a lot of voices and heads in the building.

Something will be said in the near term, he added.

“The way we look at this is: Where is there a really serious appetite for development that we need to get ahead of so we’re providing a well planned context for these development that people are seeking to effect.”

On the flip side, Golden said, there are places in the city where the building climate is so relatively stagnate that he needs to balance the agency’s efforts by focusing energy in those places – “maybe to yield zoning relief”— to prod developer interests.

“There are neighborhoods that are being left behind and that owns me at times,” he said.

Map shows Article 80 projects in the BRA pipeline

Map shows Article 80 projects in the BRA pipeline

Golden mentioned a meeting he had with State Rep. Russell Holmes last year as instructive on how the building boom is not evenly distributed.

“The representative pulled up the map of Article 80 projects on his laptop and turned [the computer] around to show me. He said, ‘Here’s all the Article 80s.’ And predictably, the downtown core had all these dots. ‘And here’s my district,’ with two dots. ‘How can I get some of that down here?’”

“That was a 30-second important lesson for me and I think about it all the time,” said Golden.

The motivation behind reforms to the city’s Inclusionary Development Policy (IDP), revised by mayoral executive order last month, is to capture more funds for affordable housing projects in neighborhoods like Mattapan— and to incentivize developers to look to “untraditional” neighborhoods as fertile ground.

Golden pointed to the development of the former Cote Ford site— a collection of city-owned parcels clustered near a future Blue Hill Avenue station on the Fairmount Line— as a sign of progress. The city-owned land will be built out into a mix of housing and retail by a collaborative of non-profit developers who won control of the site through the city’s Department of Neighborhood Development last year.

“It’s just one dot,” Golden notes, but he sees the Fairmount corridor— which was the subject of a two year BRA-led planning initiative capped in 2014 by plans for building out around each station— as having much more potential.

There’s even more reason to be bullish about growth elsewhere in Dorchester, said Golden, pointing first to plans to build out a massive residential and commercial complex next to South Bay Mall. The plan for South Bay Town Center, as its proposed by the development firm Edens, will add up to 500 units of housing, a movie theater, and a new hotel.

South Bay Town Center proposal: A rendering of the proposed South Bay Town Center project in Dorchester, which BRA director Brian Golden singles out as a “harbinger” of continued development in the neighborhood.

South Bay Town Center proposal: A rendering of the proposed South Bay Town Center project in Dorchester, which BRA director Brian Golden singles out as a “harbinger” of continued development in the neighborhood.

“The Edens project in South Bay has proven to be, I think, a healthy community process that is yielding a really positive development for that neighborhood,” said Golden. “It’s a harbinger of things to come as we progress down Dorchester Avenue. It’s the largest neighborhood in the city, with distinct parts, with distinct identities, but overall there’s a lot of promising development there. Definitely at South Bay, but then you get down to Ashmont and there are really positive, transformative projects there as well. And we’re trying to populate the world in between with other promising opportunities.

“I think the future looks really bright – not just the continuation of that pace of interest in development, but actually increasing the pace.”

Another key project still under review is known as DOTBlock, a collection of forlorn parcels at Dorchester Avenue and Hancock Street near what long-time residents know as Glover’s Corner.

Last week, as we sat in Golden’s office, representatives from the DOTBlock team were huddling with BRA planners as they continue to refine their plans before a new round of community meetings.

“We need to get the traffic right and the design right so that it interacts in a robust and healthy manner as opposed to becoming an island onto itself,” said Golden. “Making sure it’s not walled off and faces and interacts with the neighborhood around it.”

Just because the BRA board approves a project does not mean it will get built. Look no farther than Columbia Point, where a series of housing and commercial projects green-lighted by Golden’s BRA are stuck in limbo, still victims— at this writing— of a prolonged and frustrating dispute pitting the peninsula’s two preeminent landowners— the Corcoran Jennison Companies and the University Of Massachusetts— against one another. Both own large parcels around the former Bayside Expo Center, which UMass controls.

Two Corcoran projects— one for a new apartment complex and another to expand the Doubletree Hotel— are ensnared in stalled negotiations over utility lines, access rights, and other easements.

A third project— a new headquarters building for the Boston Teachers Union— is also bogged down by uncertainty with the Bayside parcels. All of this was further complicated when Bayside emerged more than a year ago as a potential site for an Olympics Athletes Village that isn’t going to happen.

The impasse on Columbia Point has Golden’s attention. “It is unfortunate and we regret terribly that there remains some cognitive dissonance that is preventing forward movement,” said Golden. “We’ve been involved in the conversations steadily for a number of years with the development parties and we seek to be an honest broker hoping to arbitrate. At the end of the day, we’re not omnipotent and we have a limited ability to resolve some of the issues.”

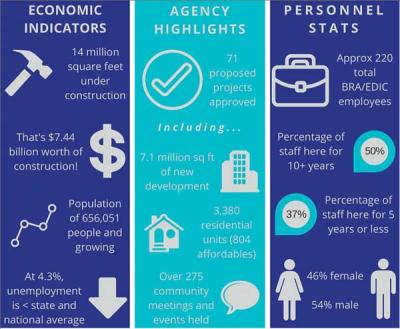

Golden’s job is to juggle these and scores of other land use issues at the height of a building boom with a team of workers that counts among the smallest in the agency’s history. Where once there were 800-plus people on the BRA’s payroll, Golden now peers down his bench at roughly 220— a squad beefed up by a score or so to respond to the surge in projects.

A snapshot of the BRA indicators 2015: From the BRA website.

A snapshot of the BRA indicators 2015: From the BRA website.

He points with satisfaction to some recent reforms on his watch: A widely-lauded website that gives real-time data on projects and planning initiatives, along with fascinating stats summarized in documents like this month’s Boston by the Numbers report. The agency — stung by two tough, self-commissioned reports that flogged its failure to collect revenue owed the city— has new software to manage its affairs and leases, helping to collect more than $5.5 million in back rents from tenants. Those lost revenues that the BRA can realize now, he says, can help fund the crucial planning needed to facilitate future growth.

The clock — that one on the Custom House that soars prominently outside Golden’s corner window— is ticking.

“I do officially now have enough experience to know how bad things can be, having arrived here in ’09,” he said. “I know that this will come to an end. We’re not going to interrupt the business cycle for very long. Is it next year or the year after? It’s coming.”

Topics: