April 6, 2016

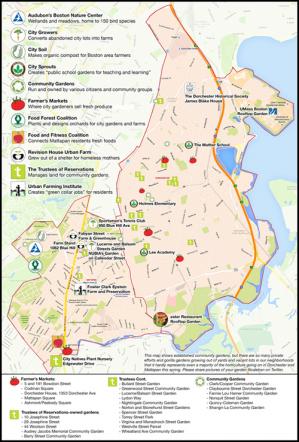

Dorchester and Mattapan: Garden and Farm Map: Click top open as PDF. Image by Caleb NelsonEven as the snow keeps falling, farmers are tending to crops growing all around Boston, toiling behind hedges and white picket fences, on rooftops, and in abandoned fields. There are roughly 175 community gardens and farms in the city of Boston, and with decades of local experience to learn from, farmers and planters are finding ways to make urban farms profitable.

Dorchester and Mattapan: Garden and Farm Map: Click top open as PDF. Image by Caleb NelsonEven as the snow keeps falling, farmers are tending to crops growing all around Boston, toiling behind hedges and white picket fences, on rooftops, and in abandoned fields. There are roughly 175 community gardens and farms in the city of Boston, and with decades of local experience to learn from, farmers and planters are finding ways to make urban farms profitable.

Urban farming efforts in Boston have been multiplying rapidly since the 2013 Urban Agriculture Rezoning Initiative established guidelines for urban agriculturalists. But, a Reporter survey shows, community gardens and urban agriculture projects have been sprouting in Dorchester and across Boston for decades.

•••

An eight-week course run by the Urban Farming Institute (UFI) attracts a group of 30 students every Thursday evening at the ABCD Center on River Street in Mattapan. Bobby Walker, who has five years of farming experience, and his partner, Nataka Crayton, spent the first few months of this year recruiting residents in Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan to attend their class, which offers a primer on the food industry to inspire new urban farming projects in Boston.

"Farming is a very big industry," says Walker. "So we try to visit many places, see aquaponics, and rooftop farms, just so people are generating ideas and not stuck in the same place."

The goal, he says, is to encourage an entrepreneurial spirit, and to demonstrate how the economy works through farming, from the soil to the farm stand to the restaurant or kitchen. Farming students who stick with the class develop business plans to create their own urban farms. There are many different ways to make money as a farmer, but it is hard work.

"We're farming as a business," Crayton says. “While we don't believe we're going to solve the job crisis, it definitely is one additional opportunity for people to build an enterprise and not just simply have to work for people, but to work for one's self.”

There are many ways of building a farming business, from cultivating an abandoned lot, building beds on rooftops, creating a greenhouse or transforming a warehouse or a freight container into a hydroponics system. The initial investment can be daunting. According to Walker, it costs around $75,000 to start up a small farm in the city, and the return on investment is slow. But the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) offers partial loans and grants to people who show commitment, and when a community works together to grow out of city-owned plots, creating a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program, some of that initial cost can be mitigated.

Excitement among Walker’s and Crayton’s students is palpable. For the ambitious few that stick around, there’s a 20-week course over the summer. During this course, students volunteer on farms for four hours a day, five days a week, earning a stipend and getting a feel for the soil. Having a business idea and having set foot on the land, they meet with counselors who have expertise in different areas to further develop their business plans. At the end of the year the class takes a field trip to an out-of-state farming conference.

The Urban Farming Institute started in 2012 by cultivating land secured by City Growers. Walker volunteered to help in the field during the first year of the program. The following year he took the class, and then became a farm manager. Students from the Institute today manage three farms in Dorchester and Roxbury: One sits at the corner of Glenway and Bradshaw streets, another is located on Harold Street in Roxbury, and the third is next to the Sportsmen’s Tennis Club on Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester where Walker started farming with City Growers on the plot behind the club.

About an acre of fenced-in land, it’s already teaming with green rows of lima beans, garlic, and Swiss chard, peeking up between snow patches. He estimates that this one plot can bring in around $10,000 a year, conservatively. Aquaponics systems can increase the yield significantly, he says. “We encourage people to come out and step on the land. You don't know what you're getting into until you really get out there. Even though it's only four hours a day, it's four hours of hard work.”

•••

One of the older farm sites grew out of the ReVision House, a family shelter for women and children that started in 1989 off Blue Hill Avenue on Fabyan street. The next year, women from the shelter started a garden on city lots next to their building and across the street. The project grew to include two greenhouses – one built over the back porches on one of their buildings, and a traditional one in the middle of their larger plot. They also maintain a farm stand at 1062 Blue Hill Ave.

The manager of the farm, Shani Fletcher, started with the ReVision House’s CSA program five years ago. She keeps the mission tacked to her wall: “To provide access to locally affordable, nutritious, and culturally appropriate food for shelter residents and our extended community.”

“We give people here access to fresh healthy food,” she says. “We grow a wide range of vegetables: peppers, tomatoes, eggplants. We have a market at Dorchester House, which is in a Vietnamese neighborhood, and so we grow different crops that are desirable for Vietnamese cooking, and there's a lot of Haitian/West Indian customers, so we also provide kale and okra.”

Inside the greenhouse across the street, Joy Gary coordinates work with several volunteer groups each week. Students from MIT were busy planting seedlings for sale to local gardeners as Gary explained: “They help with the process of either potting up things and doing things in the greenhouse, or helping us prepare the fields, or with planting or harvesting.”

Gary’s mom grew up on a farm, and her dad was a farmer in Curacao, an island in the West Indies. Their stories about living off the land, raising chickens, and eating fresh produce out of the earth inspired her to join a community garden as she was growing up in Roxbury and Dorchester.

“I went to culinary school, and so that was the tipping point for me; I realized that the food system was really messed up,” she says. “Then I found that there were a number of urban farms around the area, so I decided to just insert myself into that community, and I worked at the Food Project for a little bit and then I went to Michigan to get more in depth on farming.”

•••

Community gardening really took off in Boston in the 1970s, with Mayor Kevin H. White’s Revival Garden Program. One of the oldest community gardens in Boston, the Nightingale Community Garden on Park Street in Dorchester, was started up during that boom in community gardening efforts. It has only grown since. It is owned by the Boston Natural Areas Network, and affiliated with the Trustees of Reservations, the largest proprietors of gardens in Boston. The property includes 132 plots where Dorchester residents are already beginning to till the soil.

One of the gardeners at Nightingale, Sharon Higgins, demonstrated her worm bin at the Trustees of Reservations 41st annual Gardener’s Gathering at Northeastern University in March where hundreds of gardeners from Boston gathered in anticipation of the growing season.

She points to a patch of worms. “These are Red Wigglers,” she says. “We’re growing dirt using newspaper and composted food. Just don't put any oil in it. In the winter time you can keep it under your bed, or someplace in the house, under your kitchen sink. It has to be in a cool place.”

For the past six years she has been using the rich dirt that the worms produce to kick start her garden in the spring. “A lot of the trash that we put out, we could recycle,” she says, lifting out a handful of moist brown mixture that smelled nutty and tart, like fresh earth. “This is poop. So this is all compost."

•••

Higgins’s booth stood next to City Soil, which is a dirt farm at Audubon’s Boston Nature Center in Mattapan. “We have a contract to bring in yard waste from the city,” Chesapeake First, the site’s manager, says. “We'll turn that into as clean a product as we can for use in urban agriculture and urban gardens and farms.”

In a compost-heated greenhouse near a brook on land owned by the Nature Center, City Soil gathers bags of leaves, branches (and Christmas trees), which they turn into wood chips and compost, creating a good healthy base for community gardeners. Founded in 2012, City Soil shares its greenhouse with gardeners and organizations like the Boston Food Forest Coalition, also based at the Nature Center, who start their seedlings early in the year.

•••

Launched in 2014, The Food Forest Coalition has created perennial gardens in East Boston, Jamaica Plain, downtown Boston, and is looking at two potential sites in Dorchester. There’s a gorilla garden on Ellington Street, where neighbors started growing on a vacant lot several years ago. They want help putting in perennial fruit trees. Another garden that has been in the works for the past two years on Jones Hill is facing a bureaucratic delay.

“The city wants a budget of tens of thousands of dollars, which the neighborhood association doesn't have, and so we've been working with them,” says the coalition’s executive director, Orion Kriegman. “It's a straightforward design of a perennial garden that could fit in that space. Our focus is on edible public parks, and the value of bringing community together.”

•••

A large number of farming and gardening organizations are setting up shop these days. Many of them, like City Sprouts and the Trustees of Reservations SLUG programs, which build garden beds at Boston public schools, focus on education, providing awareness and access to fresh produce in the city’s so-called “food deserts.” Another group, The New Garden Society, offers training programs to inmates, creating prison gardens by using horticulture as a transformative tool.

Kicking off the Gardener’s Gathering last month, Mayor Marty Walsh spoke about his own connection to the land, recalling the farm in the back of his grandparents’ home in Ireland, and remembering being sent out to get carrots, onions, or potatoes.

"You make our city beautiful," Walsh said to the gathering in the university ballroom. "City government is a lot like gardening. You plant seeds, and you hope that those seeds take. As they grow you hope that the initiatives that we put out there bare fruit."

•••

The Trustees of Reservations agency is celebrating 125 years of land management in Massachusetts. Its holdings comprise 60 community garden plots in Boston on 16 acres of land. By managing community gardens, handling logistics, providing water and landscaping, it offers residents space to grow their own initiatives.

•••

Organizations like Sayed Mohamed-Nour’s non-profit NUBIA grow out of gardens owned by The Trustees. He started growing at a garden in Charlestown, and now he manages a combination of plots within seven community gardens, and two small farms in Roxbury and Dorchester over 1.8 acres in total. He donates most of the food he grows to food pantries and individuals, and last year he started selling his extra produce at farmer’s markets.

Residents like Leonide Lacet, who started gardening at at a plot in Shangri-La garden in Mattapan three years ago, share their years of horticulture experience with fellow gardeners in community gardens. Lacet, who kept chickens back home in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, also has five beds of beans, and vegetables, and Swiss chard in her back yard.

“Last year I grew just beans, all kinds of beans. I let them grow, and I still have some in my freezer. Cook them with rice, and they taste very good,” she says. Now she also helps educate and spread her knowledge as a Healthy Community Champion with the Mattapan Food and Fitness Coalition.

Vivian Ortiz, a project coordinator with the Mattapan Food and Fitness Coalition, has a vision: “With the Neponset River Greenway coming in Mattapan, we're working to get that neighborhood that's near River Street excited when it opens in the fall.” She is making connections all over the neighborhood with the Trustees and City Natives, a garden on Edgewater Drive that keeps beehives. All of the various gardening and farming efforts in Dorchester work in tandem to educate the community, and to find ways of growing gardens into small businesses.

•••

Most of the gardening efforts in Dorchester rely on grants and organizations like the Trustees for support, but the future looks bright for entrepreneurs. The Urban Farming Institute is committed to converting subsidized successes into profitable commercial enterprises by fostering a new generation of farmers in the city. UFI began with Glynn Lloyd, owner of City Fresh Foods, who wanted to figure out a way of buying lettuce locally. He started City Growers farms on vacant lots, and that enterprise grew into a non-profit focused on training new farmers on city lots. The program lasts through the summer, a whittling exercise in which 30 participants are honed to a committed team of 10 toilers of the land.

UFI’s director, Patricia Spence said the goal is to build a healthier, more stable food system in Boston. The process is underway, but it will take awhile. "You can't do it all in that 20 weeks,” Spence says. “Because we've got a big network, people will be able to work for different people in farming until they are ready to do their own thing. Eighty percent of the people who graduate stay in food, and as we amass more land, UFI will be able to actually lease them land."

A new headquarters for UFI is in the design stage, a $3 million renovation project of the Fowler Clark Epstein Farm, Mattapan’s oldest building. It will be the headquarters for classes, a small urban campus with a field out front and maybe a greenhouse out back. Bobby Walker and Nataka Crayton will be the caretakers of the property.

For now, though, it’s back to the ABCD Center where anxious students await their turns to tend the toil.

Topics: