January 21, 2016

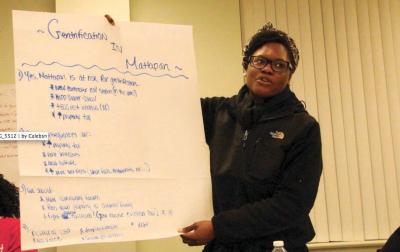

Mattapan Forum: Shavel’le Olivier of Mattapan, held a poster identifying concerns related to displacement and gentrification at a forum held at Mattapan Center for Life last Thursday. Caleb Nelson photo

Mattapan Forum: Shavel’le Olivier of Mattapan, held a poster identifying concerns related to displacement and gentrification at a forum held at Mattapan Center for Life last Thursday. Caleb Nelson photo

A forum on gentrification drew about 60 people to River Street’s Mattapan Center for Life last Thursday evening. The assembly, the latest in a series organized by Mattapan United, was abuzz with concern about displacement, with attendees swapping anecdotes about longtime residents being pushed out of the neighborhood.

Cynthia Lewis, an organizer at ABCD’s Mattapan Family Service Center, said that Mattapan United is hoping to educate and empower residents. Among those on hand for the forum were city officials who gave an overview about potential development projects and data about rising home values and rents.

Boston is the fastest gentrifying city in the U.S. according to a study done by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. To meet the increased demand for housing, part of the mayor’s housing plan is to build 53,000 homes by 2030 and those developments will also increase the demand for land in neighborhoods like Mattapan.

“Fundamentally it is a question of economics,” said Lincoln Larmon, co-chair of Mattapan United. “The state, the developers, all of these people have to be at the table, and we need to have a strategy. We need to organize around a central unified vision about how we want to move Mattapan forward, so we don’t get displaced like residents from a number of other communities throughout Boston.”

Tim Davis, the Housing Policy Manager for Boston Redevelopment Authority, gave a thorough breakdown of numbers that illustrate a growing wealth gap in Boston. Davis showed a series of maps and numbers demonstrating changes in demographics between 2000 and 2013, based on census data. (Editor's Note: Davis presented data that he compiled while at the UMass Boston Center for Social Policy. He was not representing the BRA in an official capacity at this meeting.)

Currently the highest housing costs in Boston are downtown and in Charlestown, West Roxbury and Jamaica Plain. Areas that are seeing rising housing costs include South Boston, Roxbury, and Dorchester —especially around Ashmont and Savin Hill.

Areas particularly susceptible to gentrification, Davis said, include Greenfield Street, going into Hyde Park, Blue Hill Avenue north of Woodrow Avenue, Four Corners and Codman Square. There have also been some property shifts along Morton Street and Norfolk Street.

“It doesn’t mean that gentrification is happening. It means that it’s susceptible. This is also just a starting point for discussion,” Davis said. “It’s actually important to hear from you what is going on to really know how to interpret the data.”

The room divided around seven tables to collect ideas on large sheets of paper based on four questions: 1) Is Mattapan at risk of gentrification, and if so why? 2) What are the consequences of gentrification—who gains, who suffers? 3) What should Mattapan do to protect itself from gentrification and displacement? 4) What are the consequences of not having a strategy?

Almost everyone in the room agreed that, yes, Mattapan is at risk of gentrification. The primary reasons given were the new commuter rail stations on the Fairmount Line, rent and property tax increases, an aging population and the number of vacant buildings apparently primed for development.

The consequences of gentrification listed included increased prices for services, small businesses getting replaced by chain stores, evictions and loss of culture. The consensus was that the losers in gentrification are primarily middle or low income home owners, who will be pushed out by developers and banks who benefit by buying property at relatively low prices and driving up home values and taxes.

To try to prevent that, community members suggested more community forums and education, grassroots organization, encouraging older home owners to pass down property to children and families, promoting a sharing economy —like Susu accounts‑ land trusts, organizing help for fighting evictions, and rent control.

“Gentrification is happening. Development is coming to Mattapan,” said organizer Cynthia Lewis. “We have fought for the good things that have come thus far to our community. We want to make sure that in 5-10 years we are still here with all the development happening.”

The speaking program included with a presentation by Eliza Parad from the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI), who described the organization’s land trust model. DSNI land trusts includes 226 units of housing, three urban farms, and two commercial buildings. The boards, she said, include people who live on the land trust, who make up one-third of the board; a third are residents of the neighborhood, not living on the land trust; and a third are connected to the community through businesses, organizations or churches.

These boards, she said, determine what will happen on each piece of land, and what each property should be worth over time.

“The price of the housing gets determined by what people will pay, and there’s no cap on that,” Parad said. “In a community land trust model—when you take it off of the market, and you own it as a community—the price is determined for the initial home [and] from there it has a fixed value that increases every year.”

Without a land trust, real estate agents, brokers and investors set home values, Parad said.

“If you own a home on a community land trust, it’s your home and you can decide what to do, what color to paint the inside, and if you want to do upkeep, and additions, you can do most things to it without checking in with the land trust, but nothing crazy usually,” Parad said. “You can pass it on to your children, and you can make some equity over time, but it’s capped.”

Villages:

Topics: